“If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem.” – Your Mom

Or maybe not your mom. Maybe it was your dad or a great auntie. Maybe a principal or a well-meaning member of the safety patrol. Whoever it was — someone said it to you at some point. And you got the point. Unless you’re trying to fix the problem, you are the problem. We’ve all internalized it. And since no one ever ever wants to be the problem, our natural inclination is to offer solutions, to fix it.

And then we all grew up a bit. If you’re anything like me, you became even nerdier. Maybe you even got into the chem scene (which makes chemistry sound cool, don’t you think?). If that’s the case, you may have latched onto this alternative adage — my personal favorite:

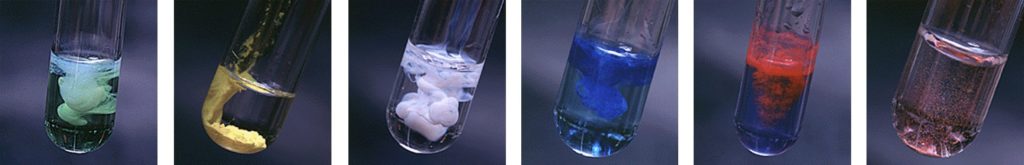

“If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the precipitate.” – All the Nerds

It made you laugh and laugh (not as much as the ether bunny or the ferrous wheel, of course), but you knew deep down that it was only a chem joke. Not a real life lesson.

Or is it?

I posit that it’s a better saying, really. More accurate for particularly complex problems, like infertility. Because to extend the chemistry metaphor a bit further — in the case of infertility, there are only two solutes in solution. My partner and myself. Anyone else can really only be part of the precipitate. A precipitate can’t fix anything, it just hangs out in the tube, separate. But that doesn’t make it part of the problem.

In the wake of our most recent crappy news, we’ve been offered a lot of love, a ton of support, and so very many ideas for next steps — ranging from “just relax” to offers of surrogacy and referrals to adoption case workers. These fixes come from a place of love, good intentions, and probably also a subconscious devotion to the first quote above. Unfortunately, it’s no one’s problem to solve. Instead, it’s Seth and my path to walk and because I know it’s hard to understand, hard not to want to fix, I thought it might be nice to share some aspects of infertility from my own perspective.

But you ain’t got no eggs!

Infertility happens for a million and one different reasons. Or even for no discernable reason at all. There’s male factor and female factor infertility. One or both partners can be affected. There can be no eggs, poor eggs, an inability to release eggs. Similarly, no sperm, poor sperm, immobile sperm. It can be mechanical — related to the shape or size or functional ability of the uterus, the shape or size of the vas deferens. It can be scar tissue, the result of surgeries, childhood radiation treatments. Genetic, chromosomal, hormonal issues. All of the above, none of the above, anything in between, or something else altogether.

We started out with “unexplained” infertility (i.e. everything seemed to be just fine). While it’s good to have nothing obviously wrong, lack of diagnosis makes treatment much more difficult — everything is just a guess at that point. However, after lots of tries (see below), we ultimately ended up with a diagnosis of diminished ovarian reserve. That means that despite being just 32 (and only 27 when we started trying to conceive), my eggs are just about out. The tank is approaching E and the few eggs I do have left are poor in quality — hence the miscarriage late last year. That’s our reason. And ultimately, it has the greatest impact on our potential solutions. So while I appreciate the offers of uteri for rent and the like, that’s not actually going to help me one bit. My body is technically quite capable of carrying a healthy pregnancy, we’re just missing half of the equation.

Grieving the loss of imaginary piggies.

Miscarrying last September was really hard. It was the most difficult experience of my life to date and the grief still comes so fiercely sometimes that all I can do is hold on and ride the wave for a while. I still had hope though, I thought that pregnancy would be followed by another. That we would have our own children. As it turns out, though, the lack of eggs means that the thing I’m really grieving is an imaginary future — one that was never going to exist, but always felt real to me in my mind. I’ve spent years wondering about the curly blonde babes Seth and I would someday bring into this world. I’ve always imagined us like Piggy and Kermit — all the girls would be pigs, all the boys would be frogs. Would they have my green eyes or Seth’s blue? My ready, beaming smile or Seth’s slower, more mischievous, lopsided grin?

And then just like that — I’ve been removed from the equation. No piggies at all. I can’t pass on the Vonck mouth. My genes won’t ever go anywhere, no matter what we decide to do next. That’s a hard pill to swallow. Something I have to wrap my mind around. Another loss to grieve, but how? There’s no memorial in the cemetery for this loss and it’s hard to know how to let it go.

All magic comes with a price, dearie.

After more than a year of trying to conceive on our own, we sought medical care for infertility and decided early on that we wanted to exhaust our possibilities to have biological children. And exhaust them we did. We’ve spent many, many, many thousands of dollars on diagnostic testing and assisted reproductive technology ranging from simple clomid and timed intercourse to intrauterine insemination (IUI) and finally two rounds of in vitro fertilization (IVF) over the course of 4+ years. Side-effects, needles, injections, ultrasounds, surgeries, procedures, tears and snot and stress and rage and bloating and month after month after month of disappointment. We did it all for a chance — all at great cost.

None of it worked for us. Now we know why. And because we’re quite certain that we do indeed want to be parents, we’re left looking at the next set of alternatives.

Egg donation, adoption, fostering. And even those options have sub-options — fresh or frozen, international or domestic, public or private. And those sub-options have sub-sub-options — how do you pick a donor? Physical characteristics? Genetics? Occupation? Personality? Psych profile? And if you adopt — are you prepared to wait for an eternity? Are you willing to let a birth parent pick you? What if they change their minds? What if you fall in love with a foster child and then they get sent back to their biological parents (Wisconsin focuses on reunification whenever possible)? Can you bare that? Can you bare any of it?

It’s a lot to think about. So much to process. And all of it — every last option — comes at great cost. Physically, emotionally, financially. On top of everything we’ve already been through, every time we hear “at least” (e.g., at least you know you did everything you could, at least you can afford it) or “just” (e.g., why don’t you just adopt?) it’s like salt in the wound — minimization of everything we’ve done so far and the difficult road ahead to family. Yes, we are fortunate that we can consider options, but that doesn’t make the necessity of considering them any easier.

It’s not you, it’s me.

The ugliest truth about infertility is that it colors everything. Over these last four years, infertility has become increasingly woven into my being and I have a hard time separating who I am from this thing I can’t do. I’m not proud to admit it, but in the face of cutesy pregnancy announcements, #blessed ultrasound pictures, and bow-decked baby bumps, happiness for those that I love and a sense of jealousy and bitterness are always there in equal measure. Of course, I wouldn’t wish infertility on my worst enemy, but that doesn’t mean I handle fertility with any kind of grace and I’m issuing a blanket apology for my poor reactions. It’s not you, honestly, it’s me. And presumably, someday it will get better, easier, to just be happy.

But here’s the most important thing: the announcements, photos, bumps, hashtags, motherhood memes — none of them have anything at all to do with me. So you shouldn’t stop doing them. It’s all worth celebrating and my scroogey attitude shouldn’t take away from that.

Conversely, radical self-care and self-preservation means that some Facebook friends are hidden and I won’t be RSVPing yes to a baby shower or making any more baby blankets for the foreseeable future. It’s too painful. I don’t ask for forgiveness or even understanding, just patience.

All roads lead to Rome.

Ultimately, there are a lot of different paths to parenthood. At present, I struggle because I don’t like any of the choices. Or, more accurately, I don’t want to have to make a choice. I will come around though. I always do, but as I said above, there’s no “just” about any of the paths. Once pregnancy via sex and waiting is off the table, nothing feels simple anymore.

In my present state of mind, egg donation proves that Seth really should have married someone else and fostering/adoption is unlikely to work out considering that even God wouldn’t choose me to raise a child — why would anyone else? Thankfully, Seth is much more capable of rational thought at the moment and I’m slowly starting to wrap my mind around some of the options. One foot in front of the other, all the way to Rome.

Not everybody wants to go to Rome.

But then again — Rome isn’t for everyone in the end. And there’s nothing wrong with making that decision for yourself. Families come in all shapes and sizes, Seth and I are a family all on our own and puppy makes three. Ultimately, though, the societal assumption is that if you’re infertile, you want to have children in any way possible and there’s the tendency to push couples struggling with infertility to pick a road and get to parenthood, one way or another.

Right now, Seth and I are pretty certain that we want to find a path to parenthood, but I think it’s really important that people accept any choices we do decide to make from the perspective of the precipitate. These things are incredibly personal and based only a little on biology, medicine, and rational thought. More than anything, we have to trust our emotions, our hearts, and each other to make the right choices for us moving forward. We both have to be on board with something 100%, no judgement if not.

The same goes for any other couple, any other family, and if you find yourself interested in learning more, I highly recommend perusing CNN’s recent infertility awareness week series. I shared this article on Facebook this morning and got a great response to it:

When you ‘come out’ about infertility

And there are several related articles written by or about couples who’ve made a variety of different choices that make great points about why people don’t talk about infertility (and why they should), how a “happy ending” to infertility can mean different things to different people, and how varied infertility experiences can be.

I’ve been spending a lot of time lately with the writing of Brene Brown and Anne Lamott and Jenny Lawson. Brave women who share their stories in an honest and beautiful way — they’ve opened me up to a whole new level of comfort in the idea of vulnerability and struggle and story telling and I think that for me, infertility is another avenue for that. The ranks of the infertile… not a tribe I’d have chosen to join, had it been a choice at all, but it’s a fierce one and I’m in good company. Someday, I’ll have a very intentional family and Seth by my side and I’ll be in good company then too. Thanks so much for being here through it all <3